Manchester Metropolitan University apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation UK.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

In some ways, the economic debate at the centre of the 2019 UK general election has come a long way from 2010, which ushered in the era of austerity. Instead of competing over who will make the biggest cuts, the two main parties are competing over who will spend the most. Yet both maintain they will be bound by a rules-based approach to spending and borrowing. Altogether, it spells a lack of vision for the UK’s economic future.

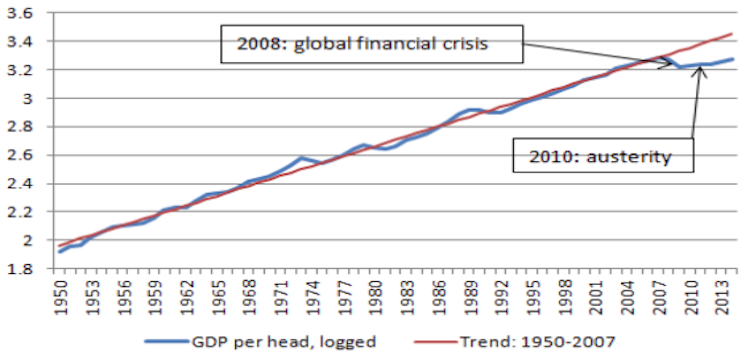

Austerity was always more of a watchword than a reality after 2010. Despite the rhetoric, the Cameron-Osborne government’s radical programme of spending cuts was put on hold after initial reductions destroyed the economy’s fragile recovery. Instead they chose to seek economic credibility precisely by reviving the rules-based fiscal policy, which ostensibly constrained public spending and borrowing levels, and which they had initially eschewed.

Benefit rates were cut, but benefit spending increased. Early narratives around economic rebalancing and reducing household debt, as well as public debt, were quickly marginalised as it became clear that short-term growth continued to depend on consumer lending and the finance and real estate industries.

And just as the delayed cuts began to peak, Osborne, followed by his successor Philip Hammond, repeatedly declared that austerity was over. The latest chancellor, Sajid Javid, made the same claim – and this time, he might actually mean it.

What has changed? A looming hard Brexit means the economy is even more fragile. Policymakers are required to take the pro-stimulus position held by most economists more seriously.

One of the relatively untold stories behind the Conservatives’ desperation for an election is that it allowed the annual budget event to be postponed. This subsequently (and controversially) allowed the government to delay the latest Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts.

The forecasts will make for grim reading – and the reality may be even worse. Most ministers probably know instinctively something that a formulaic approach to forecasting cannot really capture: winter is coming. Most voters feel the same according to polling firm IpsosMori’s Economic Optimism Index which shows a steady decline since 2014.

But it’s hard to trust either main party, or party leader, to chart a new course. The UK lacks any meaningful sense of what its economy might look like in the future, whether it’s a top-down perspective on issues such as the balance between industries, how to respond to technological change, and the extent of openness to the world economy, or a bottom-up perspective on how the economy is experienced in workplaces, communities and households on a day-to-day basis.

This explains, at least in part, commitments by the Conservatives to significantly increase public spending – mainly on public services – with spending set to rise well above 40% of GDP. While public services investment is undoubtedly much-needed, in this case it serves the political purpose of compensating for the absence of a meaningful path to prosperity. Boris Johnson’s political instincts override the small-state dogma of the Britannia Unchained cadre which dominates his cabinet.

Labour has a far more coherent plan for the economy, and has made much higher spending commitments around public investment, especially in terms of (green) industrial policy. But its approach is more radical Milibandism than radical socialism.

Crucially, it knows that a comprehensive, socialist economic strategy depends acutely on a realignment of international economic governance. But uncertainty over whether this should be pursued within, or beyond, the EU is a gaping wound at the heart of Corbynomics.

Paradoxically, despite the promised splurge, the UK political class remains convinced that economic “credibility” continues to matter to the electorate. There is a logic to this view: if there is no better future in prospect, a safety-first approach to the public finances becomes even more paramount.

So, even a much higher level of public spending is accompanied by the pretence that there are limits to the debt and deficits that might result. This surely explains why Johnson continues to make absurd claims on, for instance, the number of new hospitals his government will fund. There are no limits to his willingness to tell people what they want to hear – but there are limits to his ability to put the country’s money where his mouth is.

The main change to the limits applied in the Osborne era is that now only deficits in the current budget – ignoring investment – will be targeted. Arguably, Labour now upholds a more fiscally conservative approach than the Conservatives – in part because it recognises the severe impact a hard Brexit will have on the public finances, and in part because of its commitment to increase taxes. This will please the Treasury’s disciples of austerity, who are as concerned with raising revenue as they are with cutting spending.

On the other hand, while Labour has a rolling target for balancing the budget – a five-year plan which resets each year – the Conservatives have a fixed three-year target. This fixed approach sounds tougher, but arguably too tough to play a meaningful role in fiscal policy practice.

Both parties retain a target for reducing public debt, albeit while promising to increase borrowing significantly. The arbitrary debt targets are largely political devices, with limited economic rationale. Labour, however, will adopt the approach advocated by the Resolution Foundation, whereby public assets are used to offset public liabilities. This is crucial if the nationalisation of some industries is to be deemed compatible with fiscal rules.

UK fiscal policy is entering rather strange terrain: spending and borrowing are set to increase rapidly, while the notion of fiscal controls remains in place. Adapting the rules to economic conditions in which fiscal policymakers will be required to be more agile is ostensibly sensible, but the agenda is being mangled through the politics of Brexit and the implications of economic malaise.

Meanwhile, some of the most devastating aspects of post-2010 austerity are not addressed by the Conservatives. There are few signs of benefit cuts being reversed, or of local government funding being replenished. People become increasingly responsible for sorting out their own pensions – even as government spends more to subsidise private providers – and private debt remains both a household-level tragedy, and a major risk to the economy as a whole.

Moreover, while Labour (alone) promises to raise taxes on the wealthiest, most people will again be spared for purely electoral reasons, irrespective of the election outcome. Yet middle-class tax rises are fundamental to the UK’s fiscal sustainability, and indeed any meaningful redistribution agenda.